Universities, Solidarity, and International Boycotts.

Part I: Apartheid and the Boycott of South African Universities

By Dion Georgiou

Introduction

This is the first in a series of blogs about international movements to boycott the universities of nation states culpable of gross oppression of people within or beyond their borders, as part of a wider coordinated programme of isolation of and delegitimisation of those states. It is concerned with the ethical, symbolic, and practical objectives of such movements, the ways in which the boycotts came about and were implemented, their impacts upon the higher education systems of the states being boycotted, and the outcomes – positive and negative – of these campaigns.

It begins with an examination of perhaps the highest profile such boycott campaign, historically: that implemented against Apartheid South Africa until the eventual dismantlement of that racist political and social system in the early 1990s. Subsequent posts will examine two ongoing, unevenly implemented boycott campaigns against the universities of two states engaged in severe aggression against the populations of occupied territories and of neighbouring countries: Israel and Ukraine. A final post will draw conclusions together from these three case studies as to how and whether academic and support staff within universities, and trade unions representing them, such as the University and College Union, should presently and in future engage with the higher education systems of states involved in major violations of international law.

This post more specifically explains how Apartheid shaped the operation of South African universities from the 1950s through to the 1990s, and how this culminated in an international boycott of South African universities that was only very partially observed until the late 1980s. It also considers the arguments made for and against the boycott, before finally reflecting upon the effects the boycott did have, and how those serve to vindicate or not the cases made by the boycott’s supporters and opponents.

Apartheid and South African universities

Apartheid was the system instituted in South Africa after the Nationalist Party came to power in 1948, which segregated South Africans into four racial groups – White, Black, Coloured, and Indian – and upheld the rights of the White minority above those of other groups. It involved forms of discrimination ranging from segregation of public facilities and events to banning relationships across racial lines, disenfranchisement of non-white voters, and forced eviction of non-whites from homes and into segregated neighbourhoods. During the 1970s and 1980s, the South African government faced increasing domestic unrest and international isolation due to this policy. From 1987, the ruling National Party entered talks with the African National Congress (ANC), paving the way for release of ANC leaders such as Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990, the repeal of apartheid legislation in 1991, and full democratic elections, won by Mandela and the ANC, in 1994.

Legislation passed by the South African government during the late 1950s effectively prevented white universities from enrolling Black students, instead introducing separate institutions for different racial groups. Whereas white universities were enabled to significantly expand, and white faculty members enjoyed considerable independence as employees of University Councils, Black student numbers were effectively suppressed, while Black universities were placed under the jurisdiction of the Minister of Native Affairs, giving the state full control over their appointments. After schoolchildren played a substantial role in the Black Nationalist uprisings of 1976–77, the government agreed to some expansion of Black university education in an unsuccessful attempt to co-opt the Black middle class into passive support for the regime and help address skilled labour shortages.[1] This was, however, scarcely sufficient to meet demand for university education among the Black majority, while spending per head on Black students remained far lower than on their white counterparts.[2]

The international boycott of South African universities

The United Nations introduced resolutions from 1962 condemning apartheid and calling for the imposition of sanctions against South Africa, including restricting cultural contacts. At the same time, Black faculty and a minority of white faculty staff in the country called for an international boycott of its university system. Yet despite a spike in activity during the mid-1960s, the boycott was only very intermittently observed. In 1980, the United Nations introduced new resolutions setting out a broader set of cultural sanctions against South Africa, including a specific – though partial – academic boycott, designed to isolate supporters of apartheid in South African universities and support its opponents. This was followed by a similar set of resolutions against cultural and scientific cooperation with South Africa by both the European Community and the British Commonwealth Heads of Government in 1985.[3]

The boycott included measures including the discouragement by participating governments and institutions of academics travelling to South African universities, while foreign governments also refused to grant South African academics visas to attend conferences in their countries, and sponsoring bodies of those conferences also blocked their participation. There was also a boycott on the provision of academic books to South African libraries, with providers who did so regardless at risk of being boycotted in their own countries for doing so. Nonetheless, the academic boycott overall really gained momentum in the late 1980s, when its hitherto patchy observation became something of a scandal in and of itself, and when the ANC and the Union of Democratic University Staff Associations, formed in 1988 as non-racial body, and campaigned for a strategy of partial boycott, again with an emphasis on supporting academics who opposed government policy and isolating those who did not.[4]

Arguments for and against the boycott

Academics within South Africa who supported the introduction of a boycott hoped that it would at least increase political consciousness and agitation on their campuses, and potentially impact upon the government itself, as well as highlighting the absence of genuine academic freedom in South Africa and contributing to the wider developing sanctions regime. Its opponents among those ostensibly hostile to Apartheid were sceptical of the possibility of it being maintained, saw it as breaching academic freedom and impeding the flow of radical ideas into South Africa, and believed the government would simply ignore it in any case. The effectively selective boycott that was implemented was criticised both by critics of boycotting as still effectively limiting academic freedom, and by supporters of a fuller boycott for being impractical.[5]

Reflecting on the case for the boycott when it was at its late 1980s zenith, the Norwegian education scholar Yngve Nordkvelle put it succinctly:

In the South African context the classical academic freedoms have been seriously affected by State interventionism. It seems that the infringement has been a lot stronger for blacks than for whites. For white South African scientists autonomy was relatively strong. The claim for universalism, however, was overruled by legislation. Instead particularistic norms were imposed on them, which made free inquiry impossible.[6]

Nordkvelle rejected the conception that science – including social sciences – as practiced in South African universities were somehow neutral. Rather, he argued, science is the product of a social contract between states and scientific communities, and the racially particularistic nature of South African science was likely to shape its underlying concerns and its wider public benefits more broadly. It was therefore justifiable to exclude the South African scientific community from the broader international one.[7] He also highlighted the extent of direct state influence on scientific practice in the form of research funding, as well as the threat of reduction of those economic subsidies and implementation of other restrictions when faced with the challenge of student activism.[8] He was also dismissive of the claims of liberal academics to be doing the work of resisting Apartheid and therefore undeserving of being boycotted, given their negligible effect to date in mitigating its effects, and their broader normal participation in fields and institutions heavily shaped by racism.[9]

The effects of the boycott

Measuring the effectiveness of the university boycott and its role in ending Apartheid is difficult and perhaps ultimately impossible with any precision. Lorraine J. Haricombe and F. W. Lancaster conducted a survey of South African academics in 1990 and found that more than half of all respondents experienced some type of impact, with academics at the more internationally connected white English-speaking universities noting the effects the most, and those at Black universities the least.[10] The most commonly reported effects were refusals of academics to visit South Africa and a lack of access to resources, with variations according to subject and type of institution.[11] There were also significant minorities of academics who claimed to have had publication submissions rejected specifically due to the boycott, to have been impeded from attending international conferences, and scholars refusing to collaborate with them.[12] Generally, however, respondents tended to characterise the impact of the boycott as having inconvenienced them rather than wholly impeding their scholarly activities. Above all, they stressed its isolating impact of boycott, and the way it degraded the breadth and quality of scholarship being produced in the country.[13]

Stefanie Baumert and Jan Botha conducted an analysis more specifically of the impact of the boycott on Stellenbosch University, historically a predominantly Afrikaans-speaking university which also included several Apartheid-era prime ministers among its alumni. Between 2010 and 2012, Baumert interviewed some of the cohort of academics who had worked at the Stellenbosch during the boycott and found that while they claimed to have found it a restricting and isolating experience, further questioning revealed a more mixed picture, with continuing evidence of international collaboration, as well as a pre-existing insularity at the institution which impeded engagement even with English-language universities.[14] Moreover, statistical analysis demonstrated a continued preponderance of professors with at least some international education at the university throughout the boycott, as well as a small but growing proportion of students from outside South Africa, albeit with significant shrinking of its Western European cohort after 1985.[15] Stellenbosch also sought to counter international isolation by increasing funding for staff to make overseas research trips and for visiting academics.[16]

Such studies therefore suggest that despite being experienced impressionistically as a period of persecution and hardship, the academic boycott’s quantifiable impact, even at its height, was at best mixed. Nordkvelle too argued in 1990 that the boycott would have to attain wider participation than it had done hitherto if it were to be truly effective.[17] There are questions to be asked about whether the academic boycott, even imperfectly observed, contributed to the totality of South African cultural isolation, or whether it was simply irrelevant in comparison with more visible impacted sectors like sport and music. Given the strong relationship between the country’s universities and the state and industry, it is plausible that inhibiting the effectiveness and income-generating capabilities of South African research and development had a role to play in exacerbating the economic strains that helped compel the Nationalist government to hasten a negotiated end to Apartheid.[18] Nor, ultimately, do utilitarian arguments about effectiveness diminish the ethical reasoning for the boycott advanced by Nordkvelle:

By recognising South African science and allowing it a fully-fledged membership of the international scientific community, I think we contribute to the furtherance of an inhuman university, an inhuman science and the continuing oppression of the South African people.[19]

Dr Dion Georgiou is a modern and contemporary historian of British, American, comparative, and global politics and culture. He is currently an Associate Lecturer in History at Goldsmiths, University of London. To read more of his work, subscribe to his Substack newsletter, The Academic Bubble.

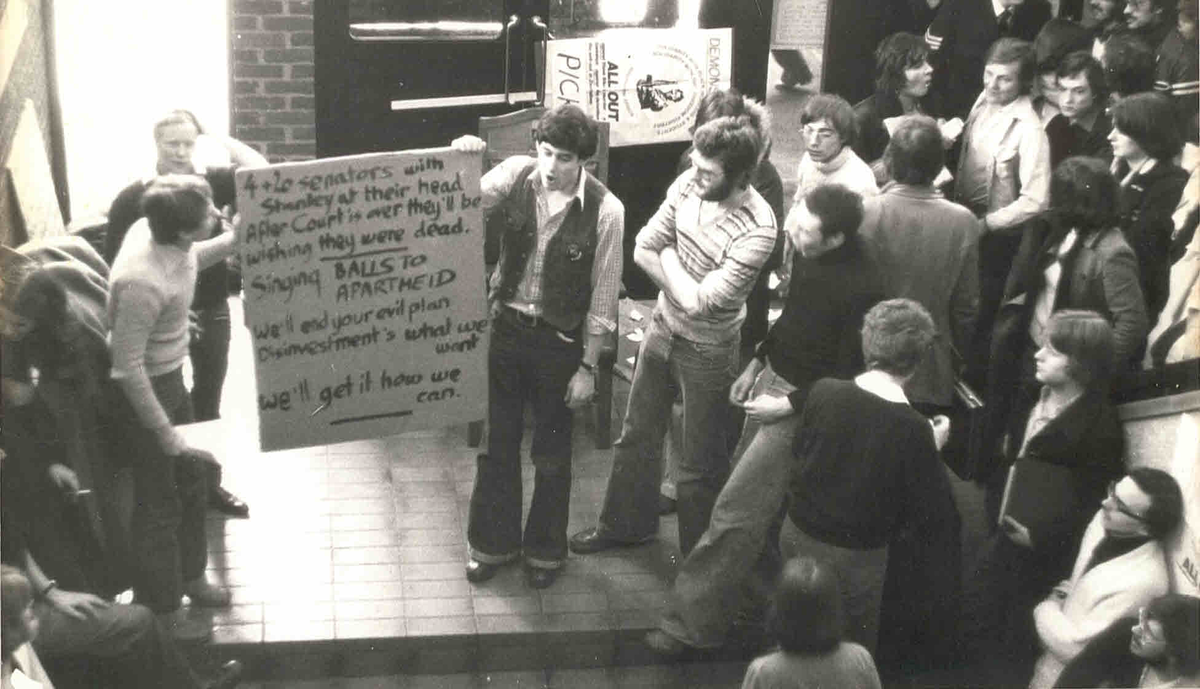

Featured image source: David Hanson, Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

[1] See Lodge, ‘Resistance and Reform, 1973–1994’.

[2] Nordkvelle, ‘The Academic Boycott of South Africa Debate’, pp. 255–258.

[3] Baumert & Botha, ‘Internationalisation at Stellenbosch University’, pp. 124–125; Haricombe & Lancaster, Out in the Cold, pp. 33–37.

[4] Baumert & Botha, ‘Internationalisation at Stellenbosch University’, pp. 125–126; Haricombe & Lancaster, Out in the Cold, pp. 37–56.

[5] Haricombe & Lancaster, Out in the Cold, pp. 30–31, 33–37.

[6] Nordkvelle, ‘The Academic Boycott of South Africa Debate’, p. 260.

[7] Ibid., pp. 260–262, 267–268.

[8] Ibid., pp. 264–266.

[9] Ibid., pp. 263, 267.

[10] Haricombe & Lancaster, Out in the Cold, pp. 70–75.

[11] Ibid., pp. 75–82.

[12] Ibid, pp. 82–93.

[13] Ibid., pp. 93–98.

[14] Baumert & Botha, ‘Internationalisation at Stellenbosch University’, pp. 125–126.

[15] Ibid., pp. 130–134.

[16] Ibid, pp. 134–136.

[17] Nordkvelle, ‘The Academic Boycott of South Africa Debate’, pp. 269–272.

[18] With 12% of government expenditure in 1987 and 14% in 1988, the government had to increasingly rely on predominantly white taxpayers to finance increasing expenditure in areas such as education. Lodge, ‘Resistance and Reform, 1973–1994’, pp. 479–480.

[19] Nordkvelle, ‘The Academic Boycott of South Africa Debate’, p. 270.,